1985 Read online

1985

1985

Anthony Burgess

A complete catalogue record for this book can be obtained

from the British Library on request

The right of Anthony Burgess to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Copyright (c) Anthony Burgess 1978

Introduction copyright (c) Andrew Biswell 2013

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

First published in 1978

First published in this edition in 2013 by Serpent's Tail,

an imprint of Profile Books Ltd

3A Exmouth House Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

www.serpentstail.com

ISBN 978 1 84668 919 2

eISBN 978 1 84765 893 7

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

to Liana

Contents

Introduction

Part One 1984

Catechism

Intentions

1948: an old man interviewed

Ingsoc considered

Cacotopia

State and superstate: a conversation

Bakunin's children

Clockwork oranges

The death of love

Part Two 1985

1 The Yuletide fire

2 Tucland the brave

3 You was on the telly

4 Out

5 Culture and anarchy

6 Free Britons

7 Nicked

8 Sentence of the court

9 A show of metal

10 Two worlds

11 Spurt of dissidence

12 Clenched fist of the worker

13 A flaw in the system

14 All earthly things above

15 An admirer of Englishwomen

16 Strike diary

17 His Majesty

18 His Majesty's pleasure

A note on Worker's English

Epilogue: an interview

Introduction by Andrew Biswell

If you had been in the United States, West Germany, France or Spain on 1 January 1984 and opened a copy of Newsday, the Miami Herald, Der Spiegel, Le Point or El Pais, you would have found an article by Anthony Burgess, which appeared under the headline '1984 Is Not Here'. In the course of a lengthy and detailed reflection on George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, Burgess examined various elements of Orwell's dystopia, and investigated the origins and context of his novel. But of course this essay was not an impartial assessment of Orwell's achievement in the genre of dystopian fiction. As most readers would have been aware, Burgess was also advertising the merits of 1985, his own book-length response to Orwell, which had been published around the world six years earlier.

Burgess's essay begins with the bold proposition that Nineteen Eighty-Four is not about the future but the past, 'a post-war Britain on to which certain fanciful things have been grafted'. He often argued in his criticism that historical or futuristic fiction is an allegory for the time in which a novel was composed. Writing in The Novel Now (1971), a survey of contemporary fiction, he makes a similar argument about the futurism of A Clockwork Orange: 'Perhaps every dystopian vision is a figure of the present, with certain features sharpened and exaggerated to point a moral and a warning.' It is clear that Burgess was referring to the ways in which left-wing ideologies of the late 1940s had been extrapolated and caricatured in the invention of Ingsoc (Orwell's imaginary political system, whose name is a corruption of 'English Socialism'). As Burgess puts it, 'Orwell felt that these intellectuals were all crypto-totalitarians, ready to lick Stalin's arse if not Hitler's.'

This is what makes Nineteen Eighty-Four, in Burgess's view, 'a fantastic satire rather than a sober forecast,' because there would never be any possibility of the English intelligentsia, meaning the readers of the New Statesman, finding themselves with political power in the real world. Burgess's interpretation is consistent with Orwell's statements in his pre-1939 writing, where he said that he wanted to save English socialism from middle-class socialists, many of whom, he believed, had never met an actual member of the working class. 'The job of the thinking person,' Orwell wrote in the final chapter of The Road to Wigan Pier, 'is not to reject Socialism but [. . .] to humanise it.' For Orwell, writing at a time of crisis, 'when twenty million Englishmen are underfed and Fascism has conquered half of Europe,' declaring himself to be a socialist appeared to be the only possible course of action.1 But his experience of being persecuted by Soviet-backed forces while fighting for another Marxist militia in the Spanish Civil War gave him cause to reconsider his allegiances, and a good deal of his scepticism about Stalinism comes through in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Burgess, in his essay, was keen to correct various misapprehensions about Orwell's novel. He was annoyed by the slapdash use of the terms 'Orwellian' and 'Big Brother' in the everyday English of the 1970s, and he made the important point (still true today) that anti-theft cameras in shops and information-gathering undertaken by corporations, though perhaps undesirable in themselves, are very different from Orwell's projection of the state looking into areas of private life where it has no legitimate business to probe. To describe the architecture of a shopping mall or an airport as 'Orwellian' was as good as meaningless. The point about Orwell's book, as Burgess identified it, is that liberty ought to mean 'freedom to make moral choices without coercion'.

It should not come as a surprise that the author of A Clockwork Orange, a parable about the importance of free will, should have been strongly influenced by Orwell's mid-century novel of tyranny and resistance. Burgess first read Nineteen Eighty-Four shortly after it was published in 1949, and, imitating Winston Smith in the novel, he wrote 'Down with Big Brother' on the title page of his diary for 1952. A search of his book collection reveals that he owned multiple paperback copies of Orwell's novels, plus a hardback volume of the Critical Essays published in 1954, the four-volume edition of Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters (1968), Orwell by Raymond Williams (1971), French and Italian translations of Nineteen Eighty-Four, and the two Orwell biographies by Bernard Crick (1980) and Michael Shelden (1991). It is evident from Burgess's notes that he had read all of the dystopian literature reviewed by Orwell or mentioned in his essays, including Zamyatin's We and The Managerial Revolution by James Burnham. By the time he came to write 1985, Burgess had been living with Orwell's novel and thinking about its implications for more than twenty-five years.

Orwell's essays and letters show that the genesis of his novel was connected to the gradual development of his thinking, over many years, about sadism, totalitarianism and power. In a letter dated 16 December 1943, he wrote: 'I think you overestimate the danger of a "Brave New World" - i.e. a completely materialistic vulgar civilisation based on hedonism. I would say that the danger of that kind of thing is past and that we are in danger of quite a different kind of world, the centralised slave state, ruled over by a small clique who are in effect a new ruling class [. . .] Such a state would not be hedonistic, on the contrary its dynamic would come from some kind of rabid nationalism and leaderworship kept going by literally continuous war.'2

One of the problems with dystopian novels is knowing how literally they are supposed to be taken. It is too easy to play the game of awarding points for accurate or inaccurate predictions: a tick for Orwell's two-way telescreens; a cross for the Anti-Sex League and the Two Minutes Hate. But it is futile to pretend that Nineteen Eighty-Four and 1985 are intended as prophe

cies about what the future is actually going to be like, or how the future looked from the perspectives of 1949 and 1978. If we ask how these dystopias seek to engage their readers on an emotional level, we can see that the genre occupies an uncertain borderland somewhere between horror, satire and cartoon. Burgess suggests that the right response to Orwell is a pleasurable shudder. Yet we should not ignore the impulse to warn which stands behind the horror: this is the way things might turn out if we fail to defend our liberties. Orwell found himself reaching for italics to make the point: 'The scene of the book is laid in Britain in order to emphasize that the English-speaking races are not innately better than anyone else and that totalitarianism, if not fought against, could triumph anywhere.'

Orwell's novel is well enough known that there is no need to summarize it here, and Burgess's pleasingly detailed discussion inevitably sends the reader back to Nineteen Eighty-Four. If it is difficult to give an account of the flavour of 1985, this is partly connected to the unusual genesis of Burgess's text. It is one of the few books that he ever wrote to commission, at a point in his career when he was feeling very uncertain-about his own fiction. In 1977 he had been working for nearly seven years on a long novel, provisionally titled 'The Affairs of Men' (eventually published in 1980 as Earthly Powers), but he was still three years away from completing it. Meanwhile, he was deeply immersed in other theatrical and screen-writing projects, including a stage musical about Leon Trotsky in New York, a Hollywood version of 'Merlin', and a television series about the military career of General 'Vinegar' Joe Stilwell. None of these sub-literary ventures came to fruition. As Burgess admits in You've Had Your Time, he was miserably depressed because he 'wanted to write a masterpiece and did not have the courage to do it'. Without his knowledge, his wife, Liana, wrote to the American publisher Little, Brown and persuaded them to commission a book about Orwell.

His decision that the book should be a hybrid of criticism and fiction was unexpected but not unprecedented: Raymond Williams ends his book on Modern Tragedy, reviewed by Burgess in June 1966, with an original tragedy of his own. Burgess began with the novella, whose working title, 'Don't Let Them Get Away With It', confirms that it was written in a state of savage indignation. But it is difficult to understand this piece of fiction without knowing something of the political and economic conditions in which it was composed. In 1976 the UK inflation rate was running at 17 per cent, partly due to high wage demands from trade unions, to which the Labour governments of Wilson and Callaghan meekly assented. To a cultural conservative such as Burgess, it seemed as if the apocalypse had arrived, and that the British government had ceased to govern. Yet the novel's hatred of strikers, punks, religious reformers and people who watch television is so intemperate that the author occasionally struggles to control his material. When he is not railing against the vulgarity of popular culture (he invents television programmes called Sex Boy and Sky Rape), he depicts striking fire-fighters looking on as a hospital burns down. It is interesting to note that, when the real-life fire-fighters went on strike over a 30 per cent pay claim in November 1977 (shortly after Burgess had completed his novella), they broke their strike to put out a fire at St Andrew's Hospital in East London. The implausibility of Burgess's plot indicates the extent of his detachment from the reality of British life in the mid-1970s.

There are a number of points of comparison between Orwell and Burgess, and the key facts of their biographies are worth considering. The most obvious similarity is that both of them discarded their original names and created new identities: Eric Arthur Blair became 'George Orwell' (borrowing the name of a minor Elizabethan playwright); and John Burgess Wilson, known to his Manchester family as Jack or Jackie, took on the twin disguises of 'Anthony Burgess' and 'Joseph Kell' when he began to publish fiction in 1956. Both of them were English outsiders who consciously remade themselves after travelling abroad. In 1922, at the age of just nineteen, Orwell joined the Imperial Indian Police in Burma, which at that time was part of the British Empire. His experience of working as an agent of colonial justice (or 'a cog in the wheels of despotism', as he put it) led eventually to a political awakening and a passionate hatred of imperialism. Having returned to Europe after five long years in Burma and established himself as a novelist and political journalist, Orwell set off on a famous journey to Wigan, Barnsley and Sheffield in 1936. His non-fiction account of unemployment in industrial Lancashire, The Road to Wigan Pier, memorably describes the background of Burgess's own boyhood in the north-west of England. As a literary critic, Orwell took particular interest in the publications of Mass Observation, an anthropological and documentary movement founded in the 1930s, which studied the social and economic conditions of working-class communities in Bolton and Blackpool. By coincidence, Burgess and his extended family were on holiday in Blackpool at the very time when the Mass Observers were there, diligently compiling reports about their drinking habits and leisure activities. 'Mass Observation,' Burgess wrote in Homage to Qwert Yuiop, 'was part of my youth.' In complicated and indirect ways, Orwell's writing about the industrial working class may be thought of as a series of encounters with the young Burgess and his early life in and around Manchester.

If Orwell's guilt about his privileged upbringing had made him want to move downwards in society - he spent time living in working-class doss-houses and deliberately modified his accent to disguise his Etonian origins - Burgess had always aimed to make the opposite journey, from the poverty and deprivation of Moss Side to a life of middle-class respectability. (It is no accident that he ended up, after his second marriage in 1968, living a life of comfortable expatriation in Malta and Monaco.) Orwell's curious desire to become a member of the working class, or at least to be accepted by working people, is called into question by Burgess's anxiousness to leave that same class as quickly as he could. Perhaps this establishes one of the reasons why he decided to set up a series of critical confrontations with Orwell in the first half of 1985, using the philosophical dialogue as his instrument of investigation and analysis.

Whereas Orwell came to despise his involvement with colonialism in Burma, Burgess was rather pleased to become an employee of the British Colonial Service in 1954, when he went to Malaya as an education officer and taught English literature at the prestigious Malay College in Kuala Kangsar (known as 'the Eton of the East'). Orwell's earlier novel about the East, Burmese Days, though it remains a fascinating document of its time, is ultimately gloomy and self-hating; but Burgess's Malayan Trilogy, now regarded as a classic in places such as Malaysia and Singapore, demonstrates his ability as a comedian of culture, who based his analysis on a broad and deep knowledge of the numerous languages of the Malay peninsula, including Malay, Chinese and Arabic. When Burgess returned to the post-colonial state of Malaysia in 1980, he acknowledged that his career as a teacher had been (as he put it) 'a kind of failure', but he remained grateful that his experience of living in the country had turned him into a writer, because the conflicts between different races and cultures had provided an abundance of material for his earliest published novels. Where Orwell had seen only despair and exploitation in the colonies, Burgess saw large cultural potential and the possibility of successful self-government, which arrived just as he was about to return to England in 1957.

Orwell's earnest non-fiction account of the disappointments and defeats of the Spanish Civil War in Homage to Catalonia is miles apart from Burgess's ironic response to the same conflict in Any Old Iron, or his presentation of the Second World War as a kind of prolonged farce in Little Wilson and Big God. Whereas Orwell, who had volunteered to fight for the Republicans in Spain, was by all accounts an efficient and welldisciplined soldier, Burgess - the reluctant conscript - took pride in his scruffy appearance, disinclination to obey orders, and general defiance of his military superiors. In many respects it would be true to say that the two men were divided not merely by politics, but by the wildly different tones and styles of their writing. If Orwell is often sermonical, politica

lly engaged and slightly humourless in his non-fiction and journalism, Burgess (as he acknowledged in his autobiographical novel, The Doctor Is Sick) can sometimes appear to place too much value on language and play at the expense of politics and social concern. It is difficult to imagine Burgess settling down to produce a work of political allegory, as Orwell did in his anti-Stalinist fable, Animal Farm. He was more at home writing a sonata for harmonica and piano, such as the one he composed for Larry Adler (the so-called 'Goon with the Wind') in November 1980. Classical music, which often has no obvious political meaning, was of very little interest to Orwell, who hardly ever mentions it in his essays on culture.

Whether or not Orwell and Burgess ever met is open to question, and most of the doubt arises from the unreliable nature of Burgess's autobiography. When Burgess was away in Gibraltar between 1943 and 1946, his first wife, Llewela, was working in London, where Orwell was involved in broadcasting propaganda to India for the BBC Eastern Service. Llewela and Orwell drank in the same Soho pubs, and she established a close friendship with Sonia Brownell, who became the second Mrs Orwell in 1949. Burgess claims, in the first volume of his autobiography, that he was on drinking terms with Orwell just after the war, and that he introduced him to Victory cigarettes, which make an appearance in Nineteen Eighty-Four, but this story deserves to be treated with caution. If it were true, it is likely that Burgess would have mentioned it somewhere in the text of 1985, and it appears nowhere else in his non-fiction writing about Orwell. What is beyond doubt is that they had a number of friends in common, and it is clear from Burgess's private diary (a more reliable source than his semi-fictional memoirs) that he got to know Sonia Orwell reasonably well in the mid-1960s, when he contributed occasional articles to Art and Literature, the cultural magazine of which she was the editor. It may be that Burgess and Orwell occasionally exchanged a nod across a crowded pub, and that their meetings were heavily embellished later on, when Sonia Orwell was no longer around to contradict Burgess's version of events. Sonia died in 1980, and Burgess published his autobiography in 1987.

A Dead Man in Deptford

A Dead Man in Deptford Honey for the Bears

Honey for the Bears 1985

1985 A Clockwork Orange

A Clockwork Orange The Doctor Is Sick

The Doctor Is Sick Earthly Powers

Earthly Powers Nothing Like the Sun

Nothing Like the Sun Collected Poems

Collected Poems The Kingdom of the Wicked

The Kingdom of the Wicked The Wanting Seed

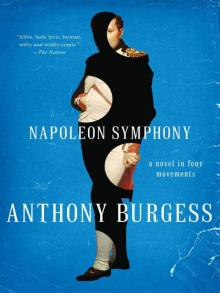

The Wanting Seed Napoleon Symphony

Napoleon Symphony The Malayan Trilogy

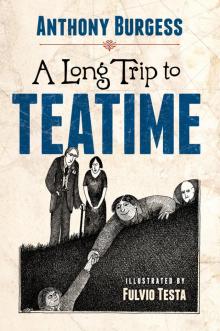

The Malayan Trilogy A Long Trip to Teatime

A Long Trip to Teatime Enderby Outside

Enderby Outside M/F

M/F The Complete Enderby

The Complete Enderby Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements

Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements Enderby's Dark Lady

Enderby's Dark Lady The Clockwork Testament (Or: Enderby 's End)

The Clockwork Testament (Or: Enderby 's End) ABBA ABBA

ABBA ABBA A Clockwork Orange (UK Version)

A Clockwork Orange (UK Version)