- Home

- Anthony Burgess

M/F Page 3

M/F Read online

Page 3

– Synchronic metaphor of the diachronic. An instant soup, as here, symbolizing the New World’s rejection of history, but in France there are still kitchens where soup has simmered for all of four centuries.

France again. The voice had a French accent and was rapid. I couldn’t see its owner, for this was a place in which, if you didn’t wish to eat in enstaged dramatic public at the huge half-wheel of the counter, you had to be nooked between wooden partitions. I was so nooked, and so was the speaker.

– Thus, a good meat broth set bubbling about the time of the League of Cambrai, bits of sausage added while Gaston de Foix was fighting in Italy, cabbage shredded in while the Guises were shredding the Huguenots, a few new beef bones to celebrate the Aristocratic Fronde, fresh pork scraps for the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle –

Masochism? A teacher of French too discursive for our utilitarian classrooms, hence poor and driven to instant soup?

– End of neck for the Jacobins, chitterlings Code Napoléon, bitter herbs for Elba.

Able, very, evidently, but this was no country for such mushy fantasy. His interlocutor seemed to reply in Yiddish – Shmegegge, chaver or something – but that was perhaps somebody else’s interlocutor. What was a Yiddish-speaker doing in a non-kosher noshery? It was time to drain my coffee and go.

– Michigan (or Missouri) oyster-stew.

– Tenderloin.

– Hash, egg.

– Ribs.

The French-accented speaker, I found, was speaking his English into a miniature Imoto tape-recorder.

– Douse the fire, cool the broth, and history dissolves into that amorphous and malodorous brewis which is termed the economy of nature –

He was plumpish, bright-eyed, probably not mad, about sixty-five, totally bald, in an expensive summer suit the colour of cassia honey, and, if by a Frenchman we mean Voltaire, Clemenceau and Jean-Paul Sartre, then he was not a Frenchman. A pair of crutches sat with him. His left hand appeared to be artificial: the fingers moved, but they had a ceramic look, dollish, or like cheap religious statuary. His bowl of soup lay quite cold on the pink formica tabletop, a faint film of grease mantling its surface. He looked at me and nodded in a kind of shy confidence. I frowned, puffing out Sinjantin smoke. The face was not unfamiliar. This did not necessarily mean that we had met before; his assumption seemed rather to be that I had seen him as a public image, or that I might be expected to have done so. Had I, in fact, glimpsed the face and caught the accent on one of those offpeak television shows that give the eccentric their brief say – flat-earthers, scrymen, royal-jellyites, mole-readers? As the maw of television must soon, if its twenty-four-hour and twenty-four-channel appetite were to be satisfied, swallow every face in the United States, so the Electronic Village would become a reality, there would be no strangers, performer would greet presumed viewer in acknowledgement of electronic contact, and there would be no one-sidedness, since viewer and performer were readily interchangeable. So I smiled faintly back, noting that he had a small black case with magnetic tape cartons in it, and that on the case was embossed in fading gold-leaf what seemed to be his name, though surely an impossible one – Z. Fonanta.

The Yiddish-speaker was, I saw now, Japanese, and his listener had a Malayalam look: no riddle there. Many a monoglot immigrant was taken on as a kosher waiter in New York and gladly learned Yiddish believing it to be English, undisillusioned by the cunning proprietor.

– A nechtiger tog!

It was, rather, a dayish night in hot tiffanied Manhattan, jewelled codpiece now but tomorrow a bare penis in blue underpants, ejaculating into Buttermilk Channel (fanciful, very, perhaps not mature imposition) or catheterized by Brooklyn Bridge. Living dildo, rather, if you saw Harlem River as of the isolating order of Hudson and East, a slim knife cutting off your manhood, white boy. Rikers Island somewhere to the right as I walked north, a tiny floating ballock with, appropriately, a Correctional Institute for Men on it. I strolled towards 44th Street, admiring the upward thrust of the masonry which pushed back the night to the limit, the new broom of the Partington Building especially, with the stubbier Penhallow Center and Shillaber Tower flanking it. I admired also the vast induced consumer appetite of this civilization, expressed in its windows and skysigns. It was safer to be bombarded by pleas to eat, drive, play or wash hair with Goldbow than put Madison Avenue and its tributaries in the service of the ideology of the ruling power. A free society.

The freedom was perhaps expressed in the act of robbery being performed, somewhere near 39th Street, by three shag-haired youths on an old man who had a rabbi-beard. There was no violence, only the urgent frisking for notes and small change of boys desperate for a fix. No kicks from mugging, no leisure to hurt save where resistance was offered. The old man knelt, crying. Some few passers-by watched with little curiosity: this was daily soap-opera of the streets. On the wall behind someone had chalked SCREW MAILER; an indifferent workman up a ladder was chipping out a smashed window in tinkles.

I have to set down my, really his, thoughts and feelings, such as they were, thus:

Hooked, and then getting fixes fulltime job, therefore work impossible even if wormholed wasted carcase, capable of coming to full life only for robbery, handing fixbread over, filling spitter, seeking skinpatch as yet unholed, were acceptable to employer. No charitable grants, state or private, for buying fixes. Robbery only way, therefore cruel, even when prudent, to interfere. Their need greater than, however needy the victim. Succour to victim after departure of thieves who fell on him? Again imprudent. Belated appearance of police or fuzz, taking in, questioning, suspicious of youth making any kind of social gesture to aged. What you have seen is a show as on television. It is an aspect of the Electronic Village. Emotions not to be engaged. We must school ourselves to new modes of feeling, unfeeling rather. It is the only way to survive. Besides, I must hurry. I have to catch that helicopter to Kennedy. It is later than I realized. The Good Samaritan was able to be good because he had time as well as money. He was travelling neither by air, nor rail, nor freeway. Amen.

So I arrived back at the Algonquin. I had left my gladstone in my room, rather than with the porter, being childishly determined to get my moneysworth. Childishly also, I intended to micturate up there without flushing the bowl, like a cat asserting its rights through smell. My urine had always been strongly aromatic. I went up; the elevatorman, a neckless Ukrainian, was frowning over baseball results in the evening paper, muttering:

– Been in centre field his throw-in’d’ve nipped dat runner at de plate.

When I unlocked the door of my room I found Loewe sitting on the bed, an arm round my gladstone as if it were a dog. Sitting on the chair was a presumed member of Loewe’s staff, though he did not look legal, rather the opposite. He wore neither jacket nor tie, and he was making loud love to a ripe peach. Splurch, imploded (not roar, which was for Loewe) wilmshpl. He had a paper bag richly juice-soaked on his lap, and peachstones lay around his sandalled feet. He nodded pleasantly enough at me, a youngish bald large man with eyes set very wide apart, like the quadrantal spheres of a binnacle. I half-smiled back, being, in a mad minor chamber of my brain, vaguely pleased that the room had not been wholly wasted in my absence. But I said to Loewe:

– How and why?

Loewe wore a white tuxedo and, a fashion too young for him, a black silk shirt with a ruched collar. He was smoking a panatella and, from his tone, seemed to be rehearsing the urbane rhythms of after-dinner conversation. He said:

– Not to cause trouble at the desk, or meet it for that matter, Charlie here opened up with a Schirmer. An instrument with an aura not merely of respectability but of positive virtue. It is in common use in the C.I.A. and the F.B.I. and other agencies of national security.

Charlie, his simple act thus ennobled, flashed teeth and peach-juice at me.

– As for why, Loewe went on, it’s to tell you that you’re not going to Castita. Not just yet, that is. I mean, one takes it that there’s no hurry. And

yet your bag is packed, as if you were hotfoot and urgent. Your mention of Castita this afternoon rang a muffled bell. I called Pardaleos in Miami. Pardaleos confirmed what had been presented to me as a mere, a mere –

– Mere susurrus of something?

Loewe ignored that, though Charlie paused in his peach-worrying to be impressed. Loewe said:

– Certain things have to be done, certain adjustments made, before you can safely voyage to the Caribbean. Trust me. Two or three days, say. Stay here. Charlie will stay with you: he has no objection to keeping awake and alert indefinitely in the service of a valued client. I’ll arrange for the bill to be sent to my office. And now, to be on the safe side, would you be good enough to hand back that money? I made a mistake, I freely admit it. A few more days, and it will be yours again.

– Look, I said, you have to freely admit that this is most unlawyerlike.

All the time, God help me, I was riddling Paradaleos and was already as far as:

Crack back, valley, and be shown

A Roman mouth, a Roman bone.

– Look, Loewe countersaid, I’ve put myself in loco parentis. Charlie here will be only too happy to be in loco fratris.

– I want to know more, I said.

– For God’s sake, Loewe said tiredly, I’ve had a tiring day and the day itself, you’ll admit, has been tiring. It’s a long story to tell, and it’s rather an upsetting story. Do what I say, there’s a good boy. There’ll be time enough to explain later. I’m late for my dinner engagement. Do hand that money over.

It was not, I knew, uncommon for lawyers to have thugs on the payroll. It was Dickensian, really. Save man from gallows and he responds with slavering lifelong devotion. Puts criminal skills or criminal violence in service of the right, which means getting people off, guilty or innocent. Weak as I was, I had to attack now. I said:

– The money’s in that bag. Safer there, I thought. Mugging and so on. Allow me to –

And I moved to the bed. To my surprise, Loewe made no objection. Charlie smiled, tilted his chair back so that the front legs hovered high above his peachstones, and then took a large mushy globe, maculate with ripeness, from the bag. Loewe was near the end of his panatella and was suddenly stabbed by the bitterness of the tar accumulated in the stub. He put it out in what was still my ashtray, making a lemony face. Charlie’s face, on the other hand, was moronically entranced by his rosary of sweetness (he’d told nearly a decade, judging from the stones). I stood above Charlie now. His new peach was at his mouth. I pushed it so that it squelched all over his muzzle. The push, weak as it was, was enough to send him and his chair (yields tender as a pushed peach – G.M.H. How exquisitely appositely a line of verse will sometimes enter the mind) over. He thudded, made a noise like ghurr, then bicycled at the air vigorously, at the same time scooping peachpie filling from his face into his mouth, as if primarily to the end of keeping the carpet unstained. I grabbed my gladstone. Loewe made no protest, either in countergrab or loud words. He merely laughed. I froze an instant in apprehension. Then I made for the door. Loewe called quite cheerfully:

– You had due warning, boy. We did our best, for God’s sake. Now you must take wh –

I slammed the door and froze another instant, this time in a kind of sickness, my eyes riveted to a framed Thurber drawing of a myopic curate admonishing a walrus. Then I started off down the stairs with my bag handy as a thrusting weapon: there might be more Loewe thugs below. As for behind me – But nobody followed.

The vestibule was crowded with people greeting each other, thumping, not seen for years (is Margie okay? Sure sure), reunion of some kind, the very best dentures that dollars could buy. A young man in levis politely pushed through, carrying a floral tribute to somebody. At the desk I said:

– My Loewe, Mr Lawyer, will be down. My name’s Faber. He’ll pay my bill.

The clerk nodded somewhat crossly, as though the paying of room-bills was a distraction from major business. At the telephone between the reception desk and the Blue Bar there was a man on crutches, talking with speed and cheerfulness. Then a woman in a floral tribute hat and with Eleanor Roosevelt teeth got in the way, saying My my my to somebody, and I couldn’t see, nor did I particularly want to see, whether it was the history soup man (I got a stupid unbidden image of alphabet pasta ready-formed into HASTINGS and WATERLOO, dissolving in broth-heat) or not. What had he got to do with anything anyway? Anyway, I had to get to Kennedy, very quick. A loud slurred voice in the bar was saying to somebody:

– And so, like I told him, Alvin slipped this disc. In Kissimmee Park it was. Know where that is?

The one addressed didn’t know, but I did; I knew far too many things like that. Outside on hot West 44th Street I stood hesitant among people wanting taxis. I couldn’t afford a taxi but I’d have to afford one. It was getting late and I wasn’t sure how often these helicopters helixed up from that roof, whichever it was. I never knew the things that were necessary. The doorman had his back to us all. He was bending to the driver of a vehicle polished like a shoe and as long as a hearse, though much squatter. The doorman then turned his soft mottled face to us and cried at a point well behind me:

– Limousine for Kennedy. Air Carib, Udara Indonesia and Loftsax.

Strange companions for my airline, but I was delighted. God bless this syndicate that gave service. The driver even got out, a dark sad dwarf with large shoulders, and slung my gladstone, light to him as a peachstone, into the baggage-trunk at the rear. It was dark inside, and there were only two other passengers. More, perhaps, would be collected at other hotels. These were two young men in open shirts, not at all dressed as for an air journey, and they were indifferent to me and to each other. The driver swung his great shoulders and his vehicle out into the traffic.

In less than five minutes I was uneasy. Every man to his own trade, but this did not seem at all a reasonable route for reaching Kennedy Airport. First, as I remembered, you had to get out of Manhattan on to the big land-slab called Queens by crossing the East River, by Queensboro or Williamsburg Bridge, I thought, or go under the river by the Midtown Tunnel. This man was driving north. Surely that was Central Park to the right. And surely this was Broadway. I had to call, nervously:

– Far be it from me to tell another man his job –

The driver ignored me but the two other passengers now became communicative. One of them even left his seat to sit next to me, breathing a kind of anchovy-sauced pizza odour as he confided:

– That’s good and right. Far far far from you, like you said.

He smiled from an open and untrustworthy saint’s face. I felt new apprehension and then turned it into shame that I’d spoken: this driver surely knew what he was doing, surely. I mumbled:

– I know there’s Triborough Bridge but that’s for La Guardia and I thought –

The other young man was now in the seat just in front, twisting to look at me, his arms folded on the seatback. Take the septum as a radius, then his nostrils were about fifteen degrees higher than normal. He said:

– Talk nabout bridges, I got this bridge, see, but it don’t fit none too good.

He opened his mouth, and four top front teeth dropped in a single comic wedge. He sucked them up again, simulating relish. The driver called, without taking his eyes off 96th Street, it must be, just ahead:

– I want those seats kept nice and clean, fellers.

– Now will be fine, Jack, said the saint-faced boy. Right here.

The limousine pulled in to the sidewalk. I said bitterly:

– From Loewe, are you?

They waved me courteously out. The bridge-boy swung my bag from the boot. They waved the driver courteously on. We stood there on Broadway by a cinema showing a film called La Forma de la Espada. There were a lot of Mediterranean types about, scuttling in the garish lights. The bridge-boy courteously handed my bag to me. I took it then, as expected, swung it towards the stomach of his companion. They were delighted. I had initiated violence. The f

irst thing they did was to wrest the bag from me, open it up, then start distributing odd articles of clothing to the dago poor. The carton of Sinjantin they split among themselves. I got very mad, as expected, and tried to belabour both of them. They laughed. The saint-faced one said:

– There’s a lot of ways out of Manhattan. Like this.

Then they started on me, while people passed indifferently by, many of them speaking Spanish. One on the Throgs Neck and another in the Robert Moses Causeway and a good crack on the Tappan Zee, two for luck on the Goethals and a final flourish on Hell Gate. That was all a prelude to taking my money. Bridge held me in a painful lock while Saint Face, as if wishing to play pocket-billiards with my balls, thrust his hands in from the rear and pulled out nearly the whole of five hundred dollars. He kissed the little bundle a big smack as if it were some precious relic, then, Bridge swinging my bag jocularly through a knot of Latin children, they made off without so much as a backward jeer.

They had not hurt me much. They had been playing on a dummy keyboard, performing a ritual obligatory before robbery, little more. Now what the hell was I to do? I counted the small change they had left in the pit of my pocket. Three dimes, four or five nickels, two quarters, several pennies and (though this had an aura of unspendability around it, like a holy medallion) a Kennedy half-dollar. There was a bar just by La Forma de la Espada. I went in and up to the long dirty counter. A man was ordering a stein.

– Yes, friend? said the bartender.

– A stein, I said.

There was a large blonde woman in a tight psychedelic-patterned summer dress, ample patches of sweat under her oxters. She stood by the counter with an empty glass that seemed to have contained an Alexandra cocktail. She looked boldly at me and said:

A Dead Man in Deptford

A Dead Man in Deptford Honey for the Bears

Honey for the Bears 1985

1985 A Clockwork Orange

A Clockwork Orange The Doctor Is Sick

The Doctor Is Sick Earthly Powers

Earthly Powers Nothing Like the Sun

Nothing Like the Sun Collected Poems

Collected Poems The Kingdom of the Wicked

The Kingdom of the Wicked The Wanting Seed

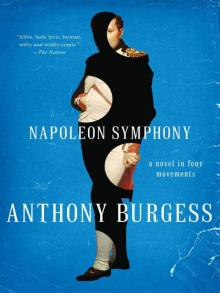

The Wanting Seed Napoleon Symphony

Napoleon Symphony The Malayan Trilogy

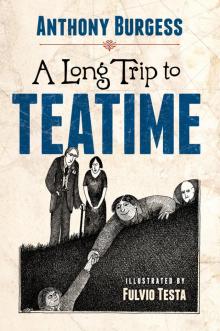

The Malayan Trilogy A Long Trip to Teatime

A Long Trip to Teatime Enderby Outside

Enderby Outside M/F

M/F The Complete Enderby

The Complete Enderby Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements

Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements Enderby's Dark Lady

Enderby's Dark Lady The Clockwork Testament (Or: Enderby 's End)

The Clockwork Testament (Or: Enderby 's End) ABBA ABBA

ABBA ABBA A Clockwork Orange (UK Version)

A Clockwork Orange (UK Version)