- Home

- Anthony Burgess

Nothing Like the Sun Page 3

Nothing Like the Sun Read online

Page 3

To it and to it and to it again

To bid his mistress come;

But an she will not he gives not a jot

For Rodney is all shot home.

The heart of WS was high and fearful, aware of his lust for this black one, her hair's and body's scents a torment to be whipped away in steady lashes of a rod to spare not. For golden-haired girls he could feel nothing, nor for carroty ones -- too like the Ardens, too like that Maundy Thursday discovery. Perhaps only in hate might he. But he did not know what hate was. Pity, yes; resentment; contempt perhaps of himself for mingling with these rough red roarers, each carrying his gross share towards the midnight feast to be eaten about fires in the clearings -- a bit of brickish cheese, pulse-bread, a leveret and a brace of stolen fowls, some filched cider in a bottle. Each with a ready rod.

As for that other and symbolical rod, the Maypole, there would soon be no more bringing home of that in Warwickshire, what with puritanical sourness and cries of out-on-idolatry; the Maypole, for all its decking with sweet-smelling nosegays and herbs, called a stinking idol. The times were on the change, the old free days being whipped fast out. But this delicate night would know mirth and, next morning, the bringing home of the great wreathed god-rod drawn by oxen, each with flowers nodding on his horn-tips. They were to go forth in small companies, into the groves and coppices, and then each group to break into primal twos, and she would be awaiting him by the cross. It was twilight, the western sky all burning argosies, the night at their backs advancing.

Noise greeted them, laughter, the thudding of an old drum and a fife's squeal, a Robin Hood horn being winded (well, here was Will the Scarlet). They were going off with their baskets and kindling and old cloaks. He saw some whose names he knew: Tapp, Roberts, little Noone, Brown, Hawkes, Diggens, and a girl for every man. But where was she?

She was there, she saw him, she was on another's arm, she laughed, waved. WS knew him, a golden youth -- Brigg or Hoggett or Haggett -- a baker's or miller's son or some such thing, as good any day as a young glover, though with a groom's face gilded with sandy flue, mouth a roaring O, eyes swine's eyes. The sonnet burned the breast of the sonneteer in shame and anger, his heart had dropped and shattered like a cold stale pasty dropped on to the kitchen flags. He tore away from his companions. They called: 'Aha! He cannot wait! He hath spilt all already!' But Dick Quiney followed, crying his name. He had seen what WS had seen, had seen him see what he had seen. 'There is a plenty more,' he said. 'She is but one.'

'Leave me.'

'I will go with you.'

'I want nobody.' He wrenched his buttons to draw out the wasted sonnet. 'Take this. You may join her list, you may buy her favours with it when she shall have done with this one.' Dick Quiney took it, wondering. WS ran. Dick Quiney called his name again but did not follow. Where could he run? Not the woods, not the church, not the duckpond, not home. The alehouse offered. He had money in his purse. The dark grew closer, the slain west's blood dripped to the nether world. The alehouse was full tonight, choked with the low and their stink, bad breath, black teeth, foul loud holes of country mouths. He saw, of a sudden, an image of proud high London, red towers over a green river with swans. He pushed himself room on a settle next to an old smocked shepherd who reeked of tar, his nail-ends swart crescents, crying rough speech in this blanketing thick air and noise to one who squinnied, thin, ancient, nodding, chumbling gum and gum ('And then what dost think a done? A laid all on board and quotha, "A groat an inch in warranty," quotha, main.') The girl who brought for him had a may-sprig in her bosom, fat, spongy tits thrust high as they were sacks on a man's back; she leered at him with country teeth. He drank. So kind, the glove-buying gentry, with a there's-for-thy-pains, the disdainful clink of wren-coin, I-thank-your-worship-and-thereto-I-touch-you-my-forelock-God-bless-your-worship. He had drunk; he would continue to drink; he had sixpence and would drink it all.

Drink ale fat growl mistress Hercules grave slue flow London dark gaggle crop. There is one that will crop no barley more. Dead of a fistula, aye. Or of a quinance, I know not certain. Fetch, I would fain. What would fain? Faith, it is all a great cheat and lie. And so saying he lets forth a rap nothing faintly.

With that, he comes to Pluto's nether gate

And Hold, saith Cerberus, what seekst thou here?

Him of the ships, saith he, and all his crew

That, bedded in the horse in Troy's confines,

Did did did

'A horse will have worms, aye, as well as your even Christian.'

He went out to piss and near fell over a dribbling drunkard who lay snoring at the moon. The moon had risen, then. He saw them in his mind's eye, buttocks moon-besilvered, rising and falling. The roar of the ale within, rage athirst for enactment, he would rail, send them on their ways stark naked, lash them with a birch-bough, sob, plain at unfaith, tear, kill. But he would drink first, drink out his sixpence.

Drink, then. Down it among the titbrained molligolliards of country copulatives, of a beastly sort, all, their browned pickers a-clutch of their spilliwilly potkins, filthy from handling of spade and harrow, cheesy from udder new-milked, slash mouths agape at some merry tale from that rogue with rat-skins about his middle, coneyskin cap on's sconce. Robustious rothers in rural rivo rhapsodic. Swill thou then among them, O London-Will-to-be, gentleman-in-waiting, scrike thine ale's laughter with Hodge and Tom and Dick and Black Jack the outlander from Long Compton. And here was one that was back to his heath after a year away, a miles gloriosus.

Hast a privy for a gob, thou, with the shit in't. Sayest? Not one fart do I give, nay, for all thy great tally. Wouldst test it, then? Thou wouldst not, for thou art but a hulking snivelling codardo. I have been in the wars and do speak the tongues of the Low Countries. Ik om England soldado. U gif me to trinken. Who saith a liar? I will make his gnashers to be all bloody. I will give him a fair crack, aye. You are but country cledge, all, that have seen naught of this world, and this one here, who is but new-wiped, he is a dizard. Thou yeanling, thou, had I my hanger I would deal thee a great flankard. But I have but my nief and that will I mash thy fleering bubbibubkin lips withal.

Loud mouth and oaths, offering to fight any there, much shotten. In galligaskins and filthy leather, his hat lost, his hair all elf-locks, he staggered toward WS. WS smiled loftily. Then with a clumsy belly-blow this bragger struck. Of a sudden, WS felt as it were a heavy-caparisoned trainband of ale given the order to march from his guts north to the moon and the gatekeeper to open up for its passage. His mouth face cheeks eye-flesh bulged bunched. And he had drunk but threepenny-worth. Nay, but there was before ... Bunched, butched, birched, birled, swirled over and out. The deck was awash. Ho there, swabbers. And thou there, avast heaving.

He was not well. He was in pain. Great seas roared inboard, the ship staggered. Ahoy, sea-room. He fought his way out, sober WS aghast at drunken Will, but he was prevented. They thrust him all about, wide black holes of laughter, to force him to return doglike to it. In his emergent poet's brain, which grew like a toadstool Jove out of that fuddled head of WS, what time shamed Will staggered and thrust to be out and off, set upon by these stinkards, verse spewed steadily forth, the spouting goddess aloof above the body's wrack.

Anon he trinks him in his jewelled garb

And decked with flowers whistles the long way out

Till that he sees the steadfast pole above

That pins the wandering heavens ...

And there he was, one that acts drunken in some silly morality, pursued by laughter as he makes his exit. And yet the act goes on offstage. He yawed and rolled, his aleship, under that very star, and saw there his own stars, his drunken initial, Cassiopeia's Chair. He lurched, and the second cohort bugled to gallop forth from his belly to the postern, out. Mewling and puking, he cried, prolonging his constellation, his unruly feet scrawling vee after vee after vee on the road: 'Mother mother mother.' It was a perilous cry.

Yet, an eternity of nothing after, he woke

warm. The dawn birdsong was deafening. He smelt grass and leaves and his mother's comforting and comfortable smell, the faint milk and salt and zest and new-bread odour of a woman's bosom. He sighed and burrowed deeper his head. His mouth was foul, it was as if he had licked rust. He squinnied, frowning, to see that the ceiling had become all leaves, that the house-beams had returned to their primal tree-state. There was white sky, in leaf-beguiled patches, over. He gave in wonder to this world a pair of tormented eyeballs. She smiled, she kissed his brow in gentleness. Her shoulders and arms and bosom were naked beneath the rough coverlet, a pair of cloaks. Beneath was some hairy blanket-like protector against the ground's damp, through which odd harmless needles of roots and stubble pricked. He was in his clothes, though they were unbuttoned, untied, in disarray. He dredged memory and found naught. It was the wood, it was Shottery, but what woman was this? To ask, when twined so in early morning and near-nakedness -- would not that be ungentle? He must needs smile back to her smile and murmur some formula of good-morrow. It would come out, he would learn all if he waited. In God's name, though, what had he done in that great void of unmemory? Never never never never never would he come more to that. He would be a moderate man. But then she whispered, in a fierce sort, 'Anon will it be full light and all stirring. Now.' And she lay upon him, a long though not a heavy woman, and it was in vain for him to protest that his mouth was not yet, not till some cleansing and quickening draught had done its office, at all ready for kissing. And so he sought to avoid her lips, lithely (though with aches and dumbed groans) turning her to the posture of Venus Observed and giving his mouth to her left breast, his stiff and wooden tongue playing about its rosy pap till she panted hard like poor Wat pursued by hounds. He arose for air, his hand now at work in darkness, an eye on each finger-end, to observe with his true, though cracked, eyes this country Venus-head, its straight bound red-gold locks, brow deep and narrow and bony, twittering scant pale lashes, the mole on the neck's long pillar gazing steadily back at his wavering light-wounded wonder, Will at work, WS thinking that perhaps he knew her (since she must belong hereabouts), though certain he had not, in the other sense, known her before. Was she not approaching carrotiness, Arden pallor? But, as the early light stretched and yawned, time spoke of the need for but one thing, and the ale's residuum, like lusty flesh-meat, fed that cock-crow Adam to bursting. ('This,' he told himself, 'is hate of her, that other, faithless with her roaring miller's son'.) And she made him like a madman, for she gripped him with powerful talons and let forth a pack of words he had thought no woman could know. So then he cracked open, going aaaaaaah, all in the tender morning, and loosed into her honey his milk, shuddering like a puppy, whinnying like a horse.

He felt, to his surprise, no shame after, no tristitia. They lay quietly as the morning advanced its little way, hid snug in their greenwood colgn. She talked and he listened, ears pricked houndlike for a clue of the quarry. '... So, saith she, if Anne will not then mayhap one of the boys, her brothers ...' So she was Anne, then, fair and English, smelling of mild summers and fresh water. She was not young, he thought: past twenty-five. She was no plum-plump pudding of the henyard, roaring the health of burning air and an ample plain cottage diet, nor was there in her voice the country twang of such as Alice Studley. The thin song of would-be ladyship (she would turn her blushing face away, no doubt, from the cock's reading) beat smartly in her neck's pulse as he fingered it. It in no wise congrued with her lying near-bare against him nor with that horrible steaming-out, some few minutes past, of a mouthful apter for a growling leching collier pumping his foul water into some giggling alley-mort up by the darkling wall of a stinking alehouse privy. What could he do but smile in secret, still queasy as he was? But he must be on his feet soon and away, saying I-thank-you-perhaps-we-may-meet-again-Anne. But he said 'Anne' softly, to taste that name in an unsisterly context, though posthumous, posthumous....

Speaking her name, it was as if he spake pure cantharides. 'Quick,' she panted. 'There is time before they are all about. Again.' She thrust bold hot long fingers, lady-smooth, down at his root in its tangled nest. 'If thou wilt not----' And she lay on him as before, to woman him, her tongue's tip near licking his little grape, her kneading fingers busy at his distaff which, all bemused, rose as it were in sleep.

And so the Maypole was brought home.

V

HE DID NOT THINK, he would not have believed, not then, that that was she who would watch over him when he slept finally not from drunkenness but from desire of death, -- else lay with eyes near-closed, sleep's feigning succubus, to watch her creaking down the stair, a groaning old crone about her housewifely tasks, busying herself with the making of sick man's broth, a cock in an earthen pipkin with roots, herbs, whole mace, aniseeds, scraped and sliced liquorice, rosewater, white wine, dates. An old quiet woman, a reader of The Good Housewife's Jewel and The Treasury of Commodious Conceits (how to make Vinegar of Roses; onion-and-treacle juice as a most certain and approved remedy against all manner of pestilence or plague, be it never so vehement), later to turn to Brownist gloom with God's Coming Thunderbolt Foretold and Whips for Worst Sinners and A Most Potent Purge for the Bellies and Bowels of Them that are Unrighteous and Believe Not. Her pots a-simmer, she would sit scratching her spent loins through her kirtle, mumbling her book.

He was in a manner tricked, coney-caught, a court-dor to a cozening cotquean. So are all men, first gulls, later horned gulls, and so will ever be all men, amen. It was easier to believe so, yet the real truth is that all men choose what they will have. After this May business he took cold and had belly-cramps and sore buttocks, and it was his body's moanings that bade him consign all of Shottery (Shittery) to hell and to say that perhaps they were right who termed maypoles stinking idols. But spring days grew longer and summer waxed and WS was ready for love again, though this time a pure love, a clean love, no more of this most demure skin or film masking a filthy bargee's lust. He threw himself at first into the work of glove-making, soothing and empty as cow's eyes, and to candled reading of North's Plutarch and Golding's Ovid and versing of his own -- dull versing, he would admit, in galloping fourteeners about Romans brought low by treachery. But one day his father bade him go to Temple Grafton to buy goatskins.

'Whateley is the man. He reads much religion and is no fool. He is from Snitterfield, like myself. Go on Brown Harry, for his fetlock is better now.'

To reach Temple Grafton he must needs skirt Shottery. 'Anne Anne Anne Anne,' the starlings scolded. He shivered on that summer's day. He knew now who she was: dead Dick Hathaway's daughter of Hewlands Farm, restive at this posthumous life of being reduced and humbled by those who were not her own kin -- the widow Joan her stepmother and three growing and bulky and bullying half-brothers. Thou art become a woman past thy first youth and yet unwed. Thou art stale goods, unwanted of any. Ho, serving-wench, fetch Harry here sweet water from the butt. WS could still feel that tenfold dig of her talons. Yet he was safe, he knew. No man, so he thought in his innocence, can be made to do what he will not. As for paternity, that risk is nulled by being shared. There was no virgin knot he had had the cutting of, unless perhaps in that dark intermission of oblivion. But that could hardly be. She had comported herself like one that knew all.

And then he found that the bird-cry of 'Anne' followed him to Temple Grafton. There, in Whateley's house (Whateley was a skinner), Anne awaited him, Anne to drive out any lingering vestiges of that other Anne, for this Anne, seventeen summers, was spring's distillation, her hair rich black and shining to mock -- in such gentleness -- the brow's snow. Her eyes were black, but they were trustful, like Dick Quiney's eyes.

'Anne,' called Whateley, yawning, flat-foot in his slippers, 'give him some wine. He is Jack's boy,' he said to his wife, 'Jack that was in Snitterfield.' And the wife, who came in cool from her dairy, smiled, a ripe and plump redaction of her daughter.

Anne, an only child, for a brother had died at birth, cut off from the world, timid, yet her eyes wide a

s she listened to this swift-tongued, spaniel-eyed poet-glover, walked with him in the garden (her parents looking on through the window, smiling, nudging: there now, he will do well, she could do worse) on his second visit. And what call you this flower, and this? Some have many names. This flower like I not, it has a smell of graves. Oh, you are too young to talk of the smell of graves. What, then, am I not too young to do? That I know not; see, I lower my eyes in bashfulness.

Is it on the fifth or seventh or ninth visit that the father and mother leave the two young people alone a space? He takes her hand, which is long and cool, and she does not ask him for it back. He sees her young breasts swell and there is a film of blood an instant before his eyes. No, not lust, not not lust. This could well be called love. He thinks: to fall in love will be Will's act, an act of Will, as to say: here I make my bed, here I choose the manner of my settling, this way I free myself from freedom's bondage, thus I escape for ever the harpy talons of lust and admit the probing of love's sweet fingers. She was untouched of man and so would remain till the clean sheets of the lavender-smelling bridal bed (and there would, he swore to himself, be no drunken snoring Toby night) should lap them both. Ah, long white hands and foot high-arching, gentle low pipe like a boy's voice. Were these, and the sweet breath of innocence, too much? If he had gone this way would he also have gone the other -- dying in New Place not unhonoured, something fulfilled? But what was it that was to be desired in life, then? Reply, reply.

A Dead Man in Deptford

A Dead Man in Deptford Honey for the Bears

Honey for the Bears 1985

1985 A Clockwork Orange

A Clockwork Orange The Doctor Is Sick

The Doctor Is Sick Earthly Powers

Earthly Powers Nothing Like the Sun

Nothing Like the Sun Collected Poems

Collected Poems The Kingdom of the Wicked

The Kingdom of the Wicked The Wanting Seed

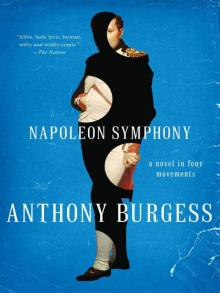

The Wanting Seed Napoleon Symphony

Napoleon Symphony The Malayan Trilogy

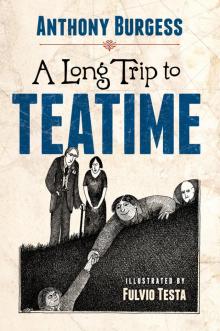

The Malayan Trilogy A Long Trip to Teatime

A Long Trip to Teatime Enderby Outside

Enderby Outside M/F

M/F The Complete Enderby

The Complete Enderby Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements

Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements Enderby's Dark Lady

Enderby's Dark Lady The Clockwork Testament (Or: Enderby 's End)

The Clockwork Testament (Or: Enderby 's End) ABBA ABBA

ABBA ABBA A Clockwork Orange (UK Version)

A Clockwork Orange (UK Version)